Billionaires seek out this doctor’s help preparing for advanced age. Here’s what he prescribes.

After the birth of his first child, Dr. Peter Attia became his own first patient in a new speciality: longevity medicine.

Today, the Stanford-trained doctor is prescribing a radical change in how Americans think about their own health care. His patient-driven, prevention-focused “Medicine 3.0” concept is designed to help people thrive in the last decade of their lives, a period typically plagued by sickness and immobility.

“The marginal decade’s not going anywhere. We will all have a final decade of life,” Attia, 52, told 60 Minutes contributing correspondent Norah O’Donnell. “My goal is to make the marginal decade as enjoyable as possible.”

Why training for the marginal decade is important

More than 90% of American senior citizens suffer from at least one chronic disease, such as heart disease, cancer, or diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The decline starts to become more severe at age 75, when Attia says population-level data shows that “both men and women fall off a cliff,” in terms of physical activity and muscle mass.

“At the population level, it’s unmistakable what happens at the age of 75. That’s what we’re up against,” Attia said. “That’s what I’m thinking about in the practice is, how do I create an escape velocity that gets somebody another 15 years there?”

60 Minutes

He tells his patients that if they don’t take preemptive action to reduce the rate of decline, they’ll operate at about 50% capacity both cognitively and physically in their final decade.

“We’re dying of heart disease, we’re dying from stroke, cancer, dementia, Type II diabetes, and we, I think, have sort of come to realize that, ‘Hey, the playbook of Medicine 2.0, which is treat a disease when a disease is present, doesn’t seem to work as well,'” Attia said. “So the first principle of Medicine 3.0 is you have to take a much longer arc on the prevention of chronic disease.”

Attia was training to become a cancer surgeon at Johns Hopkins, but got burned out performing surgery on so many patients whose illnesses were terminal. He quit with just two years remaining in his residency, and became a management consultant. After becoming a father and learning he was at risk of developing diabetes almost 20 years ago, Attia made big changes, personally and professionally.

“All I could think about was, ‘Oh my God, like, I wanna have as much time as possible on this planet with this baby'” Attia said.

The work that goes into preparing for advanced age

Attia has fewer than 75 patients, with billionaires among them. His patients pay hundreds of thousands of dollars a year to be part of his practice. Though he does not disclose the precise annual fee, he told O’Donnell that the “six-figure program” costs “much closer to $100,000 than $500,000.”

His patients’ treatment starts in Austin, Texas, where Attia is based. Their initiation includes two days of intense physical evaluation.

“I think this is the neglected part of medical testing, is how fit are you, how strong are you, how well do you move? And in many ways, these tests are even more predictive of how long you’re going to live than what I might get out of your bloodwork,” Attia said.

60 Minutes

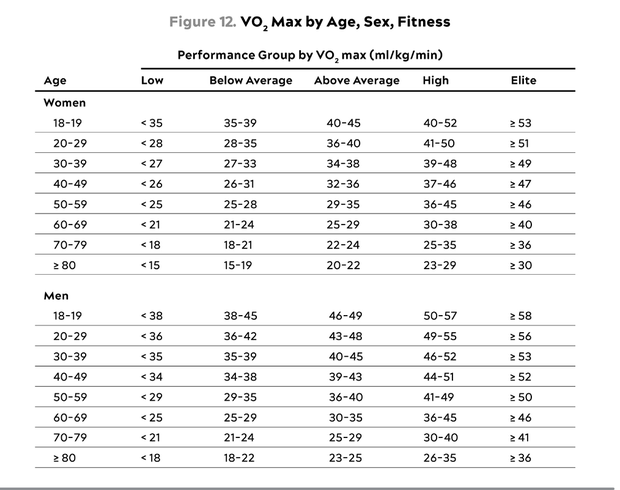

He and his team examine patients’ muscle mass, cardiorespiratory fitness and strength levels, which Attia says are more highly correlated with lifespan than even cholesterol or blood pressure. Attia says the key indicator of overall health and longevity is a test called VO2 max, which is essentially a measure of someone’s capacity to use oxygen to generate power with their muscles, heart and lungs. The test is usually completed on a treadmill or stationary bike.

The best drug to delay physical and cognitive decline is exercise, Attia said. He personally aims for about 10 hours a week, with a mix of modalities: cardio to burn fat, intense intervals for VO2 max and weightlifting to maintain strength and muscle mass.

All that exercise also comes with a recommended diet, which Dr. Attia says is needed to maintain muscle mass and prevent frailty. He wants his patients to eat about one gram of protein for every pound they weigh, every day. It’s more than double what the standard nutritional guidelines recommend.

Scans, tests and drugs

Attia also uses existing diagnostic tools, such as the DEXA scan, in novel ways. The scan, which checks bone density, muscle mass and body fat, typically costs under $300. To Attia, it’s “almost criminal negligence” that most women don’t get one until they’re 65.

In patients’ DEXA scans, Attia is looking for any indications of osteopenia — a risk for falls and frailty — as well as any buildup of fat between organs, called visceral fat, which can be linked to increased risk of both cancer and cardiovascular disease. Attia says it’s “almost criminal negligence” that most women won’t get a DEXA scan until they’re 65, because it can allow physicians to notice potential signs of bone fracture before it’s too late.

He also undergoes, and encourages his patients to get, more costly full-body MRI scans as a regular, preventative measure, noting that early detection makes it easier to treat a tumor and improve the odds of success. But he cautions patients that there is a flip side.

The American College of Radiology does not recommend preventative, full-body MRI scans, saying in a 2023 statement,”To date, there is no documented evidence that total body screening is cost-efficient or effective in prolonging life. In addition, the ACR is concerned that such procedures will lead to the identification of numerous non-specific findings that will not ultimately improve patients’ health but will result in unnecessary follow-up testing and procedures, as well as significant expense.”

“It is going to detect a lot of things that are not cancer. That means you have a lot of false positives,” Attia said. “If you’re not willing to go through that experience, as traumatic as it is, you should not engage in this level of screening.”

He also suggests patients get tested for the APOE gene, which is related to risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Attia and a handful of his patients have also used a drug called Rapamycin, FDA-approved for transplant recipients, which has extended lifespan in mice. He’s stopped the drug for now because it gave him mouth sores, which can be a side effect.

Benefits beyond exercise

For Attia, exercise carries much more than a physical benefit, even when he goes hiking with 45 pounds on his back. He says the activity known as rucking is an opportunity for him to socialize, be in nature, and to focus on his mental and emotional health.

He views that work as being just as important as the work he does on his physical health. Attia spent decades dealing with depression and anger stemming from abuse he suffered as a child, which he discussed in his best-selling book, “Outlive.” Through therapy, including two stays at inpatient care facilities, Attia says he turned a corner about five years ago.

60 Minutes

“By working hard on our physical health, we can reduce the rate of decline. But if we’re being deliberate and active on our emotional health, it can actually improve,” Attia said.

He says his progress was only possible because his wife of more than 20 years, Jill, stood by him. Multiple studies have shown the connection between longevity and having strong relationships with others.

“Just like the exercise data, I don’t think this is just a correlation,” Attia said. “I really think that there is also some causality that flows from the end of having great relationships to living a longer life.”

Will Attia’s regimen result in an extra decade of healthy life?

Attia plans on launching a digital health app called Outlive next year. He says that 80% of his program — including altering your nutrition, exercise routine and sleep – does not require a physician, and is adamant that it’s never too late to work on slowing the inevitable decline.

There are physicians, including a respected professor of public health 60 Minutes spoke with, who are skeptical about the regimen Attia prescribes.

“People are entitled to think what they want. And just because someone is a physician, doesn’t mean they’re even remotely equipped to evaluate the merits of exercise physiology,” Attia said.

In Attia’s time at the Stanford University School of Medicine, exercise and nutrition were not part of the curriculum.

“It was 25 years ago, so, maybe, things have changed. But I’m pretty sure that if you’re talking to other esteemed physicians, they’re in the same bucket as me,” Attia said. “They might not be the ones that are best equipped to be my critics.”

Attia’s not letting skeptics stop him. He’s mapped out his life with the goal of living into his 90s and having the most enjoyable last decade possible.

“I want to live to be old enough to have a meaningful relationship with as many of my grandkids as I can,” Attia said, later noting, “I know that the difference between being 80 and 90 is huge, in terms of what I can have with those kids.”